Who Gets To Be Low Class?

On raw, honest art and relentless criticism

Guns and crosses, sweat stains and grime, the vast empty landscapes of the country and the stuffy, oddly charming interiors of working class homes — all look strangely alluring on camera, captured by the same artists who shoot pop stars for magazine covers and sit front row at fashion weeks. Hung up on gallery walls and printed onto the pages of heavy photobooks sold in the heart of LES and Soho, poverty, addiction, and trauma look much less depressing and even endearing than when you are physically surrounded by them.

The charming exteriors of Art Deco motels and the no-bullshit attitude of small-town establishments make the perfect backdrop for the provocatively honest stories told by indie directors at European film festivals. There, in the comfort of the darkness, the audiences get to feel what it’s like to be a single mother fighting madness or a teenager misunderstood by their caregivers and peers. “Uniquely disarming” and “heartbreakingly beautiful” we type into Letterboxd, feeling relieved as the credits roll down the screen.

In an inverted version of watching a Hallmark movie for comfort, we dive head first into these messed up part-fiction, part-real stories looking to feel something, to be intellectually challenged — knowing full well that if things get too disturbing, we can always close the book, walk out of the gallery, look away from the screen.

I’ll be the first to say it — I am mesmerized by this type of raw, honest art. I’ve flipped through Larry Clark’s photo books, I’ve studied the fan-written Google Doc that breaks down Ethel Cain’s Preacher’s Daughter, I got a special place in my heart for The Florida Project and Bones and All. I’ve seen Tim Hursley’s photos of brothels and funeral homes, I’ve done a deep dive on SALEM, I’ve added Gummo to my watchlist. A few summers ago, I inhaled Julia Fox’s memoir detailing her tumultuous adolescence while sipping on an iced chai latte on a beautiful day in Venice Beach — the irony isn’t lost on me.

Last week, I watched Magic Farm — Amalia Ulman’s quirky comedy about a media crew from New York mistakenly landing in rural Argentina. To cover up the mishap and turn in the assignment, they manufacture a meaningless culture trend, completely missing the serious, breaking stories casually unfolding right in front of them. The characters are so comically foolish and oblivious to the life of the locals that it’s easy to roll your eyes and laugh at them. It’s tempting to see the whole thing as a spoof of the bygone era of exploitative journalism spearheaded by Vice, until you start catching glimpses of yourself on the screen.

Creatives en masse are eager to move to cities, like Paris and New York, fill their circle with people they meet at readings, showrooms, and brand dinners and throw their two cents in on things like “have we reached peak influencer trip?” — all while the stories that move us the most are happening in much less sexier places that we are effectively disconnected from. It’s easy to get so caught up in playing the game that the people and the life outside of the city become invisible until someone in the inner circle is brave enough to break out and put a spotlight on them.

That opens up a whole box of moral dilemmas: Which characters can we “platform”? Whose place is it to tell whose stories? And who deserves to “review” and offer up opinions about them? Having “the right” judgement feels urgent and all-consuming even though the art itself, and especially its subjects, rarely call for it. As indie goes mass and gets picked apart by the relentless online discourse, it feels like the artist’s mission is to offer evaluations and answer questions rather than master walking the fine line between honestly and sensationalism, documentation and exploitation, art and clickbait.

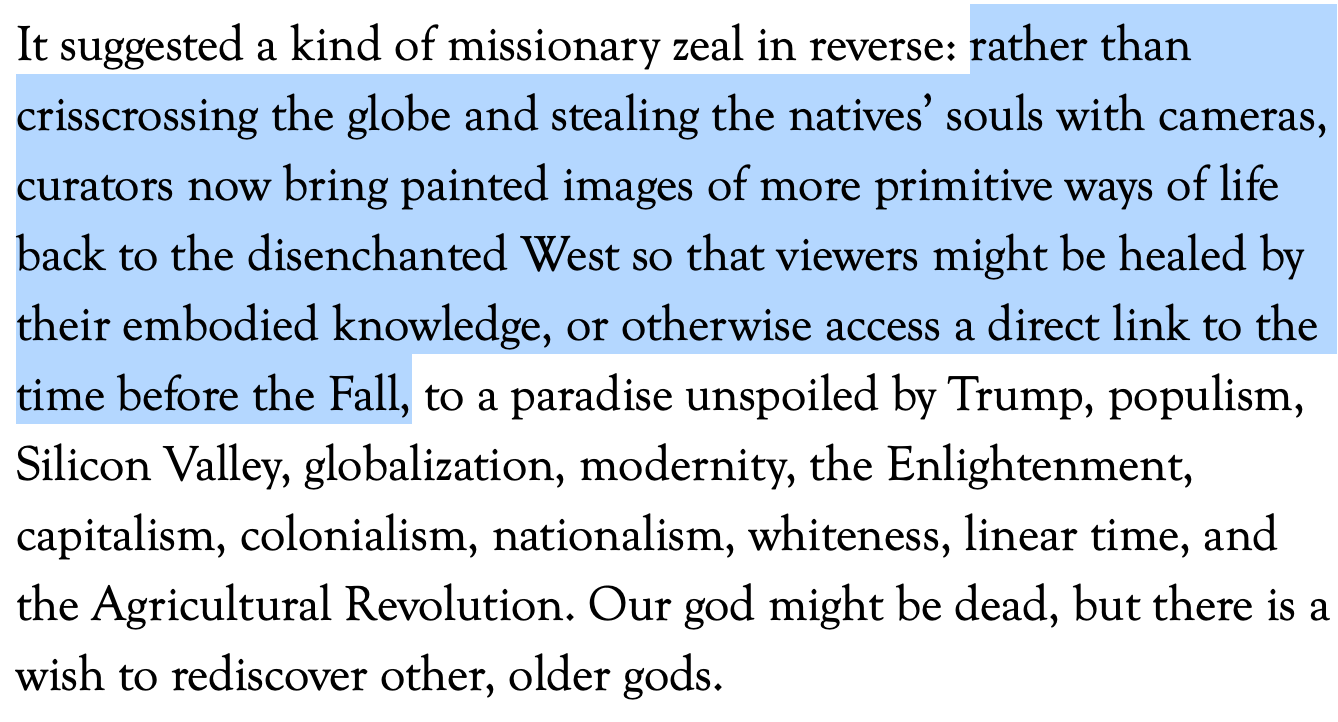

In the past five years, everything, including the brands we shop, the people we follow, and the art we consume has become political. In a memoir Health and Safety, The New Yorker reporter Emily Witt chronicles her immersion in NYC’s rave scene alongside her reporting on gun violence and police brutality during the BLM protests in 2020. In a matter of a couple of years, she goes from partying and not paying attention to the news to producing the news, the news altering her personal life, and eventually the news becoming “our only channel to perceive the world.” “There was for sure this constant and shifting map of purity tests that continues to be presented every day and that you either pass or fail. And I think the tragedy of it is that they’re very performative,” she told Interview last year. “Meanwhile, power is operating in a totally other sphere at a totally different level.”

A few months ago, for a sadly scrapped project about excessive politicization of certain objects, I spoke to a multidisciplinary artist Chivas Clem about his controversial exhibit Shirttail Kin. It features a series of intimate, mostly nude, photographs of rednecks and drifters passing through Paris, Texas — the type of men Clem used to fear as a young queer kid growing up in the South. Initially hired to help around the studio, they grew close and started posing as models for what turned into an impromptu decade-long art project exploring a whole range of complicated themes – masculinity, class, desire, addiction but also humanity, tenderness, and the duality of people’s exterior and interior.

Online, the reaction to the work was strong. Most of the men featured in Shirttail Kin are former convicts with questionable prison tattoos, posing nude, often with guns or drugs in their hands. They look like the men who Hillary Clinton referred to as “a basket of deplorables” propping up a violent, hateful regime in her controversial 2016 presidential campaign speech. There were comments about whether they deserved to be humanized. Coastal magazine writers kept asking the artist to speculate about their sexuality and politics. Ironically, the same week Shirttail Kin wrapped up at Dallas Contemporary, a group of rich, college educated men — the direct opposites of Clem’s models — proudly spread hateful ideas from the inauguration stage in D.C.

What stood out the most in my conversation with Clem is that he didn’t think of his work as edgy and radial. He has been simply photographing the people around him — the people who represent a large swath of America — trying to capture the complexity of their essence. The rest of the discourse around the exhibit was initiated by the audience and their interpretation of the photos depending on the lens they chose to apply to it.

Nonetheless, I read every line of Clem’s press circuit making sure his politics and moral compass aligned with mine. I decided not to draw attention to certain tattoos pictured in the photos mostly because it freed me up from what felt like a moral choice at the time. When my project got scrapped, I felt frustrated because I worked so hard to get things right but also a little relieved — perhaps, it saved me from criticism. I naively assumed that pre-chewing someone’s art was noble as if making people’s brains spin in circles wasn’t the whole point, as if the art couldn’t speak for itself.

IN THE MARGINS

20+ new additions to Busy Corner this week — references, talent, magazines, book stores, and more.

If you want to learn more about Shirttail Kin, I suggest reading this interview as your mind spins in circles from the very first photo you see:

I finally finished Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection which I think is a master class in walking the line between smart culture criticism and internet-induced brain rot. The “Main Character” chapter made me never want to engage in online discourse, at least in a genuine way, ever again.

And if you haven’t read Dean Kissick’s The Painted Protest essay yet, I suggest you take it for a spin this weekend. All I am going to say about it in the spirit of today’s newsletter is that it’s wild how much hate he got in the art world for what feels like a tame take to an outsider.

I have been chewing on a similar set of ideas for a piece I'm working on, specifically related to writers. This reminds me of a passage in /Normal People/ where Connell attends a book reading and feels sickened by how literature "is fetishised for its ability to take educated people on false emotional journeys, so that they might afterwards feel superior to the uneducated people whose emotional journey they like to read about."

When asked about this in an interview, Rooney says that there's a part of her that will never feel happy knowing she's just writing entertainment and "making decorative aesthetic objects at a time of historical crisis." But, she says this is THE one thing she's good at and that she *can't* do anything else. This highlights to me an interesting tension between being aware of the exploitation (this doesn't feel like quite the right word, but I can't think of anything else right now) and the tendency to keep making art about the world.

Reminds me of Sally Mann’s photographs which were also considered so controversial and poverty porn.