The "It Girl" Economy

Is the business machine behind the internet's coolest girls still on?

Gabbriette Bechtel is a polarizing figure. Some absolutely adore her and can’t get enough of her cooking videos that she films in an R&M leather apron you can shop online or an outfit sent by the featured (and often not properly disclosed) brand partner. Others are questioning her morals after she walked the Alexander Wang “comeback” show last month and went to Balenciaga’s Fall 24 show in LA. Personally, I respect the hustle (she grew from working with Savage X Fenty to YSL and Versace in under three years) but can’t stop wondering if she is getting too exposed and too commercial too quickly.

If you’ve never heard of Gabbriette, it might take a moment to figure out who she is – a model? a singer? an influencer? a food blogger? a businesswoman? The long answer is all of those things and none of those things all at once. She is…a business. She is an “it girl.”

My first encounter with the term “it girl” must have been through Devon Lee Carlson. In 2018-2021, the golden era of influencer marketing, you couldn’t escape the phone cases from her and her sister’s company Wildflower which were sent to practically everyone who posted online. In fact, I have a Wildflower case on my phone right now but sadly, I bought with my own money at an Urban Outfitters sale last summer.

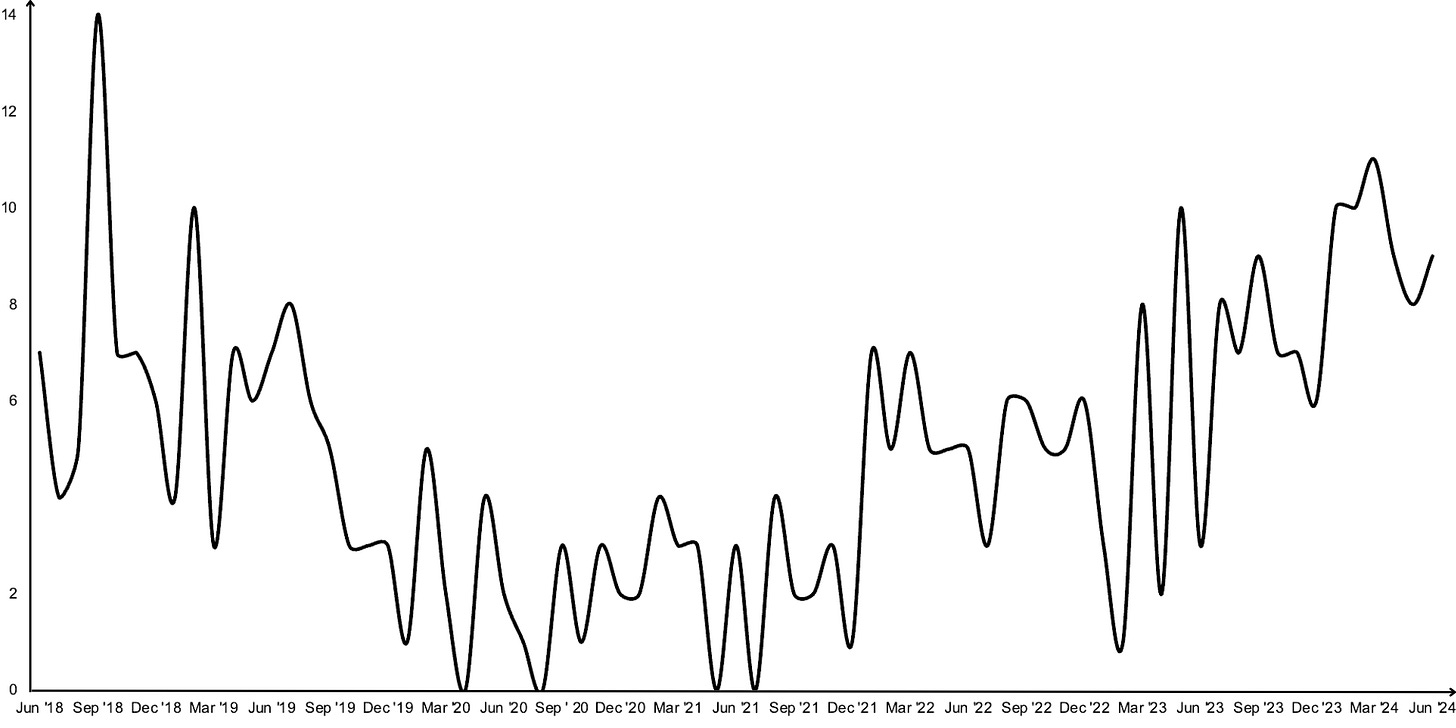

When Devon started posting online in 2013, the “it girl” economy looked very different. At least in Los Angeles, there was a clear divide between professional models and “Instagram models.” Girls like Devon got anywhere from 30k to 100k likes on an IG feed post (roughly the same amount as Vogue at the time) but could hardly even imagine working with brands that weren’t mass market, like Fashion Nova or Réalisation Par.

That changed really quickly when in 2019, luxury brands, like Louis Vuitton, Marc Jacobs, and Burberry brought the internet “it girls,” like Emma Chamberlain and Devon, on board as their ambassadors. If in 2019, that caused an uproar, working with the internet’s most famous is a common practice for brands across categories now, and “it girls” are practically ubiquitous – every pretty girls with a little following is an “it girl” to someone, every luxury brand wants to make the next “it girl” bag, and every magazine writer has written a listicle with the term “it girl” in the title, like 5 Books Every It Girl Should Read.

When New York Magazine dropped A Century of the New York 'It' Girl package last summer which cataloged the city’s “it girls” through the decades, Raven Smith responded with an essay where he questioned if the term “it girl” has lost its meaning:

“Culture has shifted. We’re all broadcasting all the time, famous in tiny circles of friends and followers. Once measured in Page Six column inches, those nebulous It qualities are more likely to be calculated in likes. I wonder if the idea of a big It girl is dying, fading from view like the northern lights? As people self-promote, as personal success becomes less and less about mass mainstream appeal, I can’t help but wonder: Are we post-It?”

Culturally speaking, maybe. But business-wise, the “it girl” currency has never been stronger. The one thing that the New York Magazine’s issue makes abundantly clear is that at the time when getting crowned as the “it girl” meant the most culturally, it was also extremely fleeting and exploitative financially. Rare cases, like Chloë Sevigny and Jemima Kirke, aside, being a downtown celebrity got you cool stories, press, and material for a possible memoir, but didn’t automatically turn into modeling contracts and zeros in your bank account.

When in 2014-2016 the Girlboss movement emerged, women started not only purposefully building personal brands online but also positioning these brands to speak to other women rather than men. While the internet’s biggest “it girl” Alexis Ren still posted in bikinis (nothing wrong with that by the way), downtown New York “it girls” Leandra Medine Cohen and Emily Weiss were posting funky “man repeller” outfits and intricate wedding prep routines. The Girlboss movement didn’t solve the gender inequality in business but it clearly showed which demographic spent more money online, and brands across categories quickly picked up on that. Being an internet “it girl” became very lucrative not only for the girls but also everyone around them.

Some brands, like Réalisation Par, became synonymous with “it girl” or as they call it, “dream girl” marketing. They’ve had an ongoing partnership with Devon Lee Carlson since 2017 and relentlessly reposted the same three pictures of Jeanne Damas, Alexa Chung, and Bella Hadid wearing their tiny dresses on Instagram. By the time I decided to splurge on one of their silk dresses myself in 2021, they have been seen on everyone from Kaia Gerber and Nicola Peltz to Zoe Kravitz and Emrata. Other brands, like Parade, famously relied on a network of micro “it girls” – cool downtown celebrities with a little internet following, until they graduated to shooting Julia Fox and Sydney Sweeney in their campaigns.

As the internet became more saturated with pretty girls posting ads for all kinds of “it girl” brands, and companies, like Parade struggled financially, it raised questions around the viability of “it girl” marketing. At the same time though, a similar model still works really well for brands whose margins can afford it, like Reformation and Sezanne, and even luxury brands like Miu Miu, Tory Burch, and Balenciaga. And who knows, if the board didn’t push for Parade’s explosive growth and then suddenly cut its oxygen as the DTC boom slowed down, it could have come out on the other side – accounting for 10-30% of total revenue, Parade’s community program was a money-making machine.

In fact, “it girl” marketing is still so lucrative that there is a whole infrastructure that exists to facilitate the relationship between the girls and the brands. When a downtown New York talent agency No Agency started as a modeling agency in 2016, the prominent modeling agencies, like IMG, still ran a traditional modeling business that managed faces and bodies that can be used in ad campaigns and runway shows. No Agency’s proposition was to pluck out and develop hybrid talent from the streets of downtown New York – pretty girls who split their time between arts, corporate gigs, modeling, and posting online. Eight years later, this no longer sounds like a novel idea, and the big modeling agencies are well-adapted to support multi-hyphenate talent, like Gabbriette (who worked with No Agency until around 2020).

Can a true “it girl” be commercial through? Isn’t she supposed to be different from an influencer? That’s what I tend to think when I look at girls like Sofia Richie Grainge and Alex Cooper. But are the women that I do put on the “it girl” pedestal, like Sofia Coppola or Bella Hadid really that different? In the two years alone, Sofia Coppola finally joined Instagram and launched an eye kit, a jewelry collaboration, a cashmere capsule, a Uniqlo drop, and a tinted lip balm. Bella Hadid has been using her account to promote her fragrance brand Orebella among other things.

And why shouldn’t they? By now, the people in the industry understand that their Instagram accounts are business entities that exist pretty much separately from them. The only difference between them and other “it girls”, like Rachel Sennott or Ayo Edebiri, who choose to convert their status into movie rather than brand deals, is that everyone online sees the deals they make. Who knows what’s happening behind the scenes though?

Maybe as consumers enter The Great Exhaustion and stop responding to influencer marketing, charisma, talent, and befriending cool people will replace the follower count as the premier “it girl” business package. Until then, diversify your brand and “it girl” assets and take advantage of the “it girl” boom until it busts. I wouldn’t be putting all my money on red, but why not take advantage of the lucky cards you’ve been dealt? That is, of course, not financial advice.

IN THE MARGINS

A couple more things from me this week:

I am updating the Busy Corner Reference bank and Writer Rolodex, as well as adding a new guide this weekend. It’s your last chance to take advantage of the friends & family code ILY this weekend.

Loved Annie Kreighbaum’s guest lecture in Feed Me earlier this week. After piloting a massive creator program for a consumer startup last year, I think this is spot on:

“A dream hire for me would be a hyper social, hyper considerate relationship manager (with great taste) who could actually form bonds with influencers and know their birthdays and communicate and do thoughtful things outside of campaigns, when we’re asking them for something in return. It seems like relationship management is the most important thing when it comes to top-tier influencers (those with large, engaged followings who are proven to convert). Otherwise, most consumer brands will get more bang for their buck by scaling a gifting program of just free product for content creators of any size.”

A must read from Amy Odell about WGSN’s Great Exhaustion Report. Some delicious bits:

"By 2026, de-influencing and no-shopping challenges will morph into an even bigger movement to slow our consumption and shop mindfully instead of for a quick fix."

"The stealth wealth trend is here to stay, as rich people seek to hide their money from those who are struggling in the face of exacerbated inequality."

"Some of us will become acutely concerned with fighting against misinformation, which will only become a bigger problem thanks to AI. This will lead consumers to have even less tolerance for marketing spin from brands, such as greenwashing."

Super interesting…I actually took note when Vogue’s latest interview with Suki Waterstone labelled her an ‘it’ girl and thought the language was quite dated? (also barely remember her being an IT girl because she was so young!) ‘It girls’ in the U.K. tended to mean women with means that didn’t work and just partied and were on ‘the scene’. It was quite the negative connotation 15 years ago!

I am obsessed with how well researched and informative this was. Despite being chronically online I find myself shocked at how many of these women I didn’t know. Loved this post from you