The cult of the artful lifestyle is robbing you of a life in the arts

On aspirational marketing, curation as procrastination, and art as luxury

Every fashion and design brand that markets itself as aspirational tells a similar story about what a perfect day looks like — wake up in a room that resembles a booth at a Scandi design fair, head down to the nearest cafe to do a little reading over a pour-over and a flaky pastry, then loiter around a familiar route of galleries and vintage shops, blending into a crowd of pretty people in penny loafers and cashmere. Depending on where you are, you see a different spin on it — more whimsey, more beachy, more brutalist. But the core remains the same — a soft, balanced life that values taste, learning, and a broad definition of creativity.

This particular flavor of aspiration is regarded as more sophisticated than a life of a filthy capitalist, more mature and enlightened than a neurotic hustle of an ambitious upstart although similarly, it cares less about who you are and what you do, and more about the theatrics of how you present yourself — what you wear, where you travel, who you are seen with. It frames a thoughtful media diet and a tasteful shopping list as the prerequisites to a fulfilling life and a successful creative career but glosses over the process of actually achieving either because it’s designed to sell the dream, not help you fulfill it. Curating an artful lifestyle has been elevated to an art form, and for many, it became a form of procrastination that stalls them from pursuing serious art projects.

An artful lifestyle comes with the type of quick and constant reassurance that’s hard to come by in the arts. One of my favorite directorial debuts of the year, Lurker, captures this in a story about a vintage store clerk Matthew who infiltrates the inner circle of a budding music star Oliver through a mix of luck and online stalking. It starts out as a typical quest to make it in LA, full of awkward scenes, testing an outsider’s ability to blend in. And then, instead of evolving into a heartwarming story about taking risks and creative soulmates, Matthew’s “fake it till you make it” plot line derails into a fucked up psychological horror. He is so fixated on becoming a number two in someone else’s career that making art on his own isn’t even an option — not so much for the lack of drive or talent, as for the unique sense of validation and confidence that Matthew finds only in proximity to Oliver.

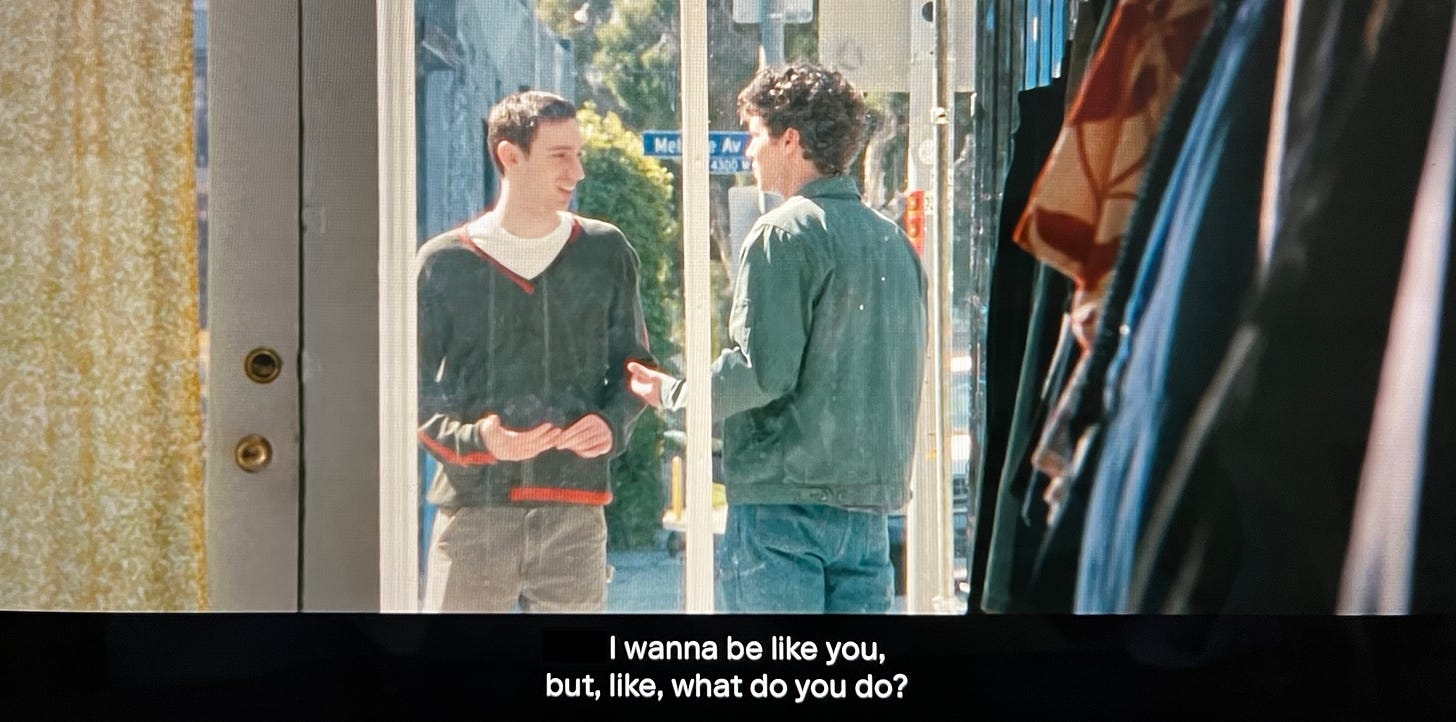

Whatever Matthew does creatively, whether it’s shooting simple B-roll or directing Oliver’s music video, is ultimately just a means to making personal connections. The art itself carries very little intrinsic value to him — it’s worthless unless it’s recognized by someone like Oliver. There is only one scene where Matthew pauses to consider that the hollowness of his creative practice may be the very reason why he struggles to build genuine relationships. As he makes it up the ranks of Oliver’s entourage, he is approached by a fan on the street who gushes over his sceney outings and calls him his hero and then catches him off guard with a simple question. “What do you, like, do?” says the fan with child-like naivety. “Or…I wanna be like you but, like, what do you do?” he adds quickly, picking up on a sudden change in Matthew’s demeanor. Since Matthew leans on art as a crutch in his quest for validation and connection, scrutinizing his achievements means poking holes in his relationships and ego.

People, like Kendall Jenner, are meticulous about the way they decorate their houses and the type of books they display on their coffee tables because that is what sets them apart from their vulgar friends and families. Audiences are inspired by the “rich who rich right” by patronizing small businesses and dressing in understated outfits because it’s a guilt-free way to admire wealth. Every fashion and design piece that is remotely artistic and well-made has a luxury price tag, and it’s increasingly unclear who the high margins benefit more — the artists or the shareholders.

When the mainstream media framed an artful lifestyle as aspirational, it painted a picture of a future where people en masse are flocking to the arts, but so far, all it seems to have accomplished is create a new strand of consumerism. Like many other aspirational tropes across sports, politics, and Hollywood, the artful lifestyle, as constructed by brands and influencers, is rooted in strategic accumulation of wealth rather than expertise and excellence. Conversations about art get drowned out by red carpet critiques and step-by-step guides to developing personal taste that give rise to the “performative” archetypes rather than a new and larger creative class.

Having seen a peek of a more equatable future — one that’s concerned with enabling fast and safe public transit rather than getting a fit off on a subway platform — serious creative audiences are tuning out the noise created by luxury fashion shows and engagement bait published by culture magazines, in favor of voices that prioritize connection over status. It’s only a matter of time until The Row feels as dated as Mar-a-Lago and reading culture essays is as corny as stacking non-fiction on your nightstand. We’ve got to stop pinning the same five pictures and ideas to a moodboard and go make stuff. It’d be a shame if we let the trap of an artful lifestyle rob us of a chance to build a life in the arts.

IN THE MARGINS

Brenda Weischer’s notes on breaking the habit of consuming more than you produce:

“i know that the most wasted times of my life have been those of worrying about something i either can or cannot change, comparing myself to a shiny life I see through my screen, waiting for an idea, a chance, someone’s attention, improvement, change when i could have just moved the needle myself. and that is also creation, doing something, anything. i know that all of the extraordinary that i seek for my life, kind of already exists within me, i just have to start creating it. how can i label myself overly ambitious but spend my nights scrolling through other people’s work?”

Mickey Galvin is one of the many people whose work has inspired this essay. She makes YouTube videos that range from vlogs to culture criticism and just put out her first short film.

If you haven’t yet, listen to that NYT interview with Kristen Stewart that went viral a few weeks ago. Besides an overall weird power dynamic between the two, at some point, Kristen turns the host’s random philosophical question back at him which prompts him to reluctantly confess that he regrets not having the guts “to try and be an actual artists.” Chills.

Love this. Reminds me of a book I just read — Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico, a book about a millennial couple who live and create a life based on aesthetics and external validation from sharing those aesthetics which ultimately result in a quite empty and soulless life.

Thank you for your brain, love reading how you express this topic so so much (as always) x

really good insights here! i agree with a lot but i think there’s a sensual dimension to an artful lifestyle that can enhance an artists practice rather than detract from it, and that is in part what makes the promise so romantic

outside of the influence of branding and aspirational content, i believe there is an authentic desire to commune with life in a way that is artful, at the root, as human being

maybe that’s the balm to the problem, really. to remember / return to the felt states that created these aesthetics so long ago… cafe culture in paris, for example. which didnt become popular among artists because they wanted to have aesthetic spreads on a cute bistro table but because it was a place where you could trade ideas for hours, drink and smoke to keep warm while writing in the cold, etc etc

just my optimistic expansion (: great read. very thought provoking