Luxury's Gone Mass, Mass's Gone Luxury

Where does this leave fashion consumers?

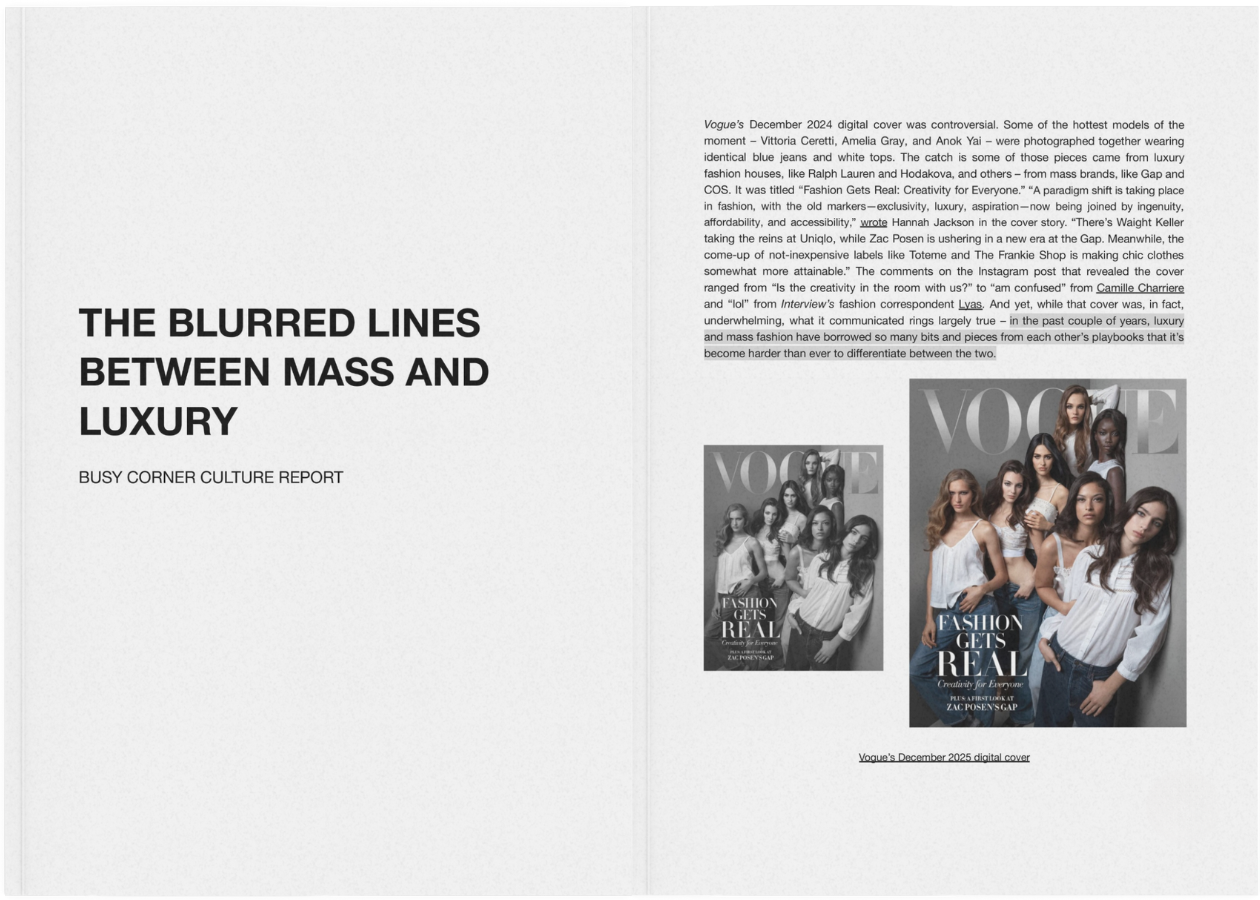

Vogue’s December 2024 digital cover was controversial. Some of the hottest models of the moment – Vittoria Ceretti, Amelia Gray, and Anok Yai – were photographed together wearing identical blue jeans and white tops. The catch is some of those pieces came from luxury fashion houses, like Ralph Lauren and Hodakova, and others – from mass brands, like Gap and COS. It was titled “Fashion Gets Real: Creativity for Everyone.” “A paradigm shift is taking place in fashion, with the old markers—exclusivity, luxury, aspiration—now being joined by ingenuity, affordability, and accessibility,” Hannah Jackson wrote in the cover story. “There’s Waight Keller taking the reins at Uniqlo, while Zac Posen is ushering in a new era at the Gap. Meanwhile, the come-up of not-inexpensive labels like Toteme and The Frankie Shop is making chic clothes somewhat more attainable.” The comments on the Instagram post that revealed the cover ranged from “Is the creativity in the room with us?” to “am confused” from Camille Charriere and “lol” from Interview’s fashion correspondent Lyas. And yet, while that cover was quite underwhelming, what it communicated rings largely true — in the past couple of years, luxury and mass fashion have borrowed so many bits and pieces from each other’s playbooks that it’s become harder than ever to differentiate between the two.

While prices for luxury goods continue to increase, more and more brands are under fire for reports of unethical production practices and ridiculously high markups. “We’re not buying things for what they are but for what they represent,” Katie Thomas, head of Kearney’s Consumer Institute, told BoF. “The main thing you’re paying for now is the label on the front.” Pieces from Rick Owens, Dries Van Noten, Jacquemus, and Hermés can be purchased through Walmart’s third-party resale platform and pieces from cool girl brands, The Row and Khaite, show up at discount retailers, like T.J.Maxx. Once worried about damaging their reputation by working with mass fashion brands, luxury fashion talent – designers, models, business executives, and influencers – have been taking leadership roles and partnership deals from fast fashion brands. Clare Waight Keller, ex-Artistic Director at Chloé and Givenchy, became the Creative Director of Uniqlo after partnering up with them on a capsule collection in 2023. Zac Posen, founder of a namesake brand and one of Hollywood’s favorite red carpet gown designers, joined Gap Inc. as their CD. And a whole slew of luxury fashion designers have partnered with mass fashion brands on capsule collections – Jonathan Anderson and Uniqlo, Glenn Martens and H&M, Stefano Pilati and Zara. That, in turn, attracted A-list talent, like Kaia Gerber, Cindy Crawford, Kate Moss, Alex Consani, and Charli XCX, as well as high-profile influencer talent, like Enya Umanzor and Nara Smith, all of whom have worked with the brands. But most importantly, the public response to these partnerships has been largely positive, or at the very least confused, with very few people speaking up against their favorite creatives working with fast fashion brands. “i’ve been thinking a lot about the hierarchy of ethical consumption, what stores are and are not considered fast fashion… is j.crew “okay” to shop from? is COS just a slightly more expensive zara? a lot of “cool” people shop at uniqlo so it must be fine, right?” writes emily north in her newsletter angel cake. “i fear the exhausting merry-go-round of metrics deciding what is or isn’t okay to wear is causing people to just say “fuck it” and buy whatever they want morallessly.”

In the meantime, mass fashion brands have been taking pages from the luxury fashion’s playbook and prioritizing creativity and self-expression over quality and sustainability (or lack thereof) conversations in their marketing strategy. Uniqlo was featured in Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers last summer alongside the costumes designed by Loewe’s Jonathan Anderson. David Lowery, the filmmaker behind A Ghost Story and The Green Knight, directed Zara’s first live fashion event for Zara Streaming which featured Cindy Crawford and Kaia Gerber and was essentially a higher-budget QVC stream where shoppers could purchase pieces that the models were trying on. In fall 2022, Zara and Kaia Gerber co-hosted a Paris Fashion Week afterparty, attended by Karlie Kloss, Eve Jobs, Moncler’s CEO Remo Ruffini, and Vogue Paris’s Emmanuelle Alt. Pull&Bear became an official sponsor of London Fashion Week, and COS has been hosting shows in New York, London, and Milan since 2021, winning back the wardrobe space in the closets of fashion editors, creative directors, and other downtown influencers. Gap adopted the haute couture vs ready-to-wear model with GapStudio – red carpet gowns and capsule collections designed by their newly appointed creative director Zac Posen. “If Louis Vuitton can have ball gowns that they don’t produce on a red carpet in order to sell luggage,” he told Vogue in December, “why can’t Gap have a T-shirt gown on the red carpet? But we’ll actually produce it.” Posen was talking about Anne Hathaway’s Venice Film Festival look that according to him, was a real viral moment for the company although Gap wasn’t ready to divulge the exact numbers in press. What sounds like a solid business strategy though is actually a step backwards for the brand – in 1996, Sharon Stone famously wore an off-the-rack Gap turtleneck to the Oscars as a testament to the quality and cultural relevance of the brand.

In some cases, brand marketing strategies that were initially created by luxury fashion brands to expand their brand universes, have even drastically changed their meaning when co-opted by mass fashion. For example, both Alaïa and Zara recently opened branded cafes. But if for Alaïa, this is a tried-and-true way to invite more people into their world, for Zara - it's mostly an attempt to elevate their status since their core offering is already widely accessible. Similarly, mass brands launching resale is as much of a nod to sustainability as it is a brand exercise aiming to replicate the excitement around archival fashion that luxury benefits from.

There was a time when mass fashion brands developed iconic marketing shticks to differentiate themselves from the competition on factors that are more sustainable than price and speed – the Abercrombie store scent and homoerotic catalogues, the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show, and the Gap dancing commercials. Of course in retrospect, half of those tactics turned out to be problematic but they shaped the DNAs of these brands just as much as they shaped American culture. Now that threatened by the rise of ultrafast fashion, they are switching gears and producing minimalistic garments, working with high-status talent, and competing over the approval of the creative class alongside their luxury counterparts, it’s become difficult to not only tell them apart from each other but also make financially and socially responsible decisions about where and how to shop.

How did we end up in a place where buying a $2,000 bag or a $9,000 sweater doesn’t guarantee that it was made sustainably out of high-quality materials? Why, unlike Abercrombie, Sezane, and Reformation – brands whose business model caters directly to an average consumer and leans heavily into affiliate and influencer marketing – Zara, H&M, Gap, and Uniqlo are aiming to elevate themselves to the luxury level? And why it might just work? What does it take for a fashion brand to be culturally relevant? And why are consumers flocking back to high street brands despite sustainability concerns? The answers to these questions reveal just as much about the current state of fashion as they do about the shifting meaning of luxury and mass across beauty, hospitality, and other neighboring industries, especially because for the past decade or so, it’s been one of fashion’s biggest missions to absorb all of them into its business.

CHAPTER ONE: LUXURY INFLATION

Walking out of The Row’s FW24 show that caused a bit of a stir in Paris by asking their guests to refrain from using their phones, The Washington Post’s fashion critic Rachel Tashjian, wrote something that has stuck with me for a while: “Chewing my madeleine and pondering my phoneless experience, I was transported back to the time, long before this era, when fashion was a subculture that demanded connoisseurship…looking back at the magazines, reviews and shows of the time, it seems that a lot of women — and not just big spenders — looked at fashion as something between a cult and a dating service. They were obsessive but also skeptical, in pursuit of an understanding of a designer’s vision.”

It’s hard to imagine the time when fashion was a niche artful hobby when every other person on your feed is a fashion influencer and you can barely walk a block in any major city without spotting the trending item of the season – a jelly shoe, a Le City Bag, and the oval Miu Miu glasses. “Fashion has never been more relevant in mainstream popular culture than now,” wrote Tony Wang and Michael Yeung in 1Granary. “From viral red-carpet fashion moments during the Challengers press tour to Super Bowl athletes striding into Allegiant Stadium decked out in runway outfits, fashion has become a key component of the public’s fascination in our biggest cultural moments across all spheres.”

Last week, the biggest fashion conglomerate, LVMH, reported €84.7B in 2024 revenue which means that their business grew more than eight times since 2001 when they reported just above €10B. Prada-owned brand Miu Miu has grown exponentially since its turnaround in 2020, reporting unbelievable numbers in 2024 – 89% YoY growth in Q1 and a whopping 105% YoY growth in Q3. Hermes grew from just over $1B in revenue in 2001 to €11.2 in revenue for the first nine months of 2024, and Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsens’ The Row reached a $1B evaluation.

A lot of this explosive growth came as a result of what Wang and Yeung called hyper-oprimitzation, Thom Bettridge called merchtainment, and Rachel Tashjian called the marvelization of fashion – prioritizing the broader idea and the theater of luxury fashion over its niche cultural essence and products. The most cited and clear examples of this are LVMH appointing Pharrell as the Creative Director of Louis Vuitton over an industry insider, François-Henri Pinault, the owner of Kering, buying the Creative Artists Agency (CAA), and YSL launching a film production company. But there are plenty of other examples of this throughout the industry – from brands, like Jacquemus, whose viral fashion shows, marketing campaigns, and spaces often overshadow its products, to brands like Telfar and Balenciaga, whose conceptual design and experimental marketing exist in an ongoing conversation with the broader cultural movements and popular discourse. Hyper-optimization goes beyond tapping star entertainers for seasonal campaigns or sponsoring artists, creative residencies, and foundations and sets culture creation across fine arts, music, film, sports, publishing, and other spheres outside of fashion as the top strategic priority of the brand. Broadening their direct cultural reach, fashion houses open up infinite new opportunities for monetization all while making their original products – clothing and accessories – desirable to a larger audience at a higher markup.

The only catch is that when luxury fashion houses open themselves up to a mass audience and lean heavily into the mainstream culture, they risk diluting their creative points of view and lowering the bar on craftsmanship so much that they start losing brand differentiation and alienating their core dedicated audience. Narratives and content take precedence over creativity and products that pull customers in with exceptional quality and attention to detail rather than buzz. “When fashion houses vie to become cultural protagonists at this scale, it signals a complete inversion of what luxury represents,” write Tony Wang and Michael Yeung. “Today, the output of luxury fashion houses is closer to a mass consumer good than it is to a true luxury good, as luxury brands constantly churn out new products, collaborations, content, and activations to become as relevant to as wide a demographic range as possible.”

Louis Vuitton, Balenciaga, and Burberry are all good examples of this. Wang and Yeung cover in their research how Burberry’s numerous collaborations with everyone from Gosha Rubchinskiy to Minecraft led to Everything Everywhere All At Once-ification effect of the brand which stirred up short-term excitement but failed to modernize it. A brand consultancy and creative studio NEMESIS broke down how with Demna taking over the reigns at Balenciaga, the brand became “a form of vore porn” that consumes stars, symbols, and subcultures and spits them out as ironic designs instead of cultivating original house codes. Interview’s fashion correspondent Lyas made a harsh but fair comment about Louis Vuitton. “We all know that the only thing that Pharrell is bringing to Louis Vuitton is his name. Because when people can’t remember your clothes, you make them remember your face,” he said pointing to the silhouettes of Pharrell’s and Nigo’s side profiles on one of the jackets featured on the AW25 runway. And while all of this doesn’t necessarily translate into an immediate decline in revenue - Demna’s Balenciaga, for example, performs consistently well, luxury fashion’s rapid expansion into every other bordering sphere of culture is starting to prompt questions among its core customers. When you buy a Louis Vuitton bag now, are you buying a piece of history the same way as when you buy a Loewe Puzzle bag or are you buying a piece of Pharrell’s merch that represents a bygone high fashion streetwear era?

A CLOSER LOOK AT THE BLURRED LINES BETWEEN MASS AND LUXURY

“We all know that the only thing that Pharrell is bringing to Louis Vuitton is his name. Because when people can’t remember your clothes, you make them remember your face,” — Lyas.

“As average luxury prices continue their climb, we’re all now finding treasure troves in the hallowed halls of mid-market labels — Uniqlo, Gap, Banana Republic, J Crew, Cos — that trend-forward, style-minded people had, for the most part, dismissed over the past decade or so. It’s not that everyone stopped shopping at these brands. It’s that the gap between luxury and everything else widened, leaving behind a customer base that aspires to invest in fashion but cannot afford ‘luxury’,” — Jose Criales-Unzueta.

“Zara is clearly building a platform where they can empower emerging designers, and even creators, influencers and celebrities. The next major fashion group might come from a high-street brand – the next LVMH or Richemont or OTB Group,” — Tony Wang.

“Sustainability, once a hot buzzword, has become a liability for many brands, with consumers wary of greenwashing. Values-driven messaging is increasingly viewed as preachy, rather than aspirational; limited drops of innovations that never scale have become routine, rather than exciting. At the same time, brands are grappling with a broader cultural vibe shift, especially in the US, where a backlash against “woke capitalism” has prompted many businesses to pull back from public commitments to diversity and sustainability,” — Sarah Kent and Malique Morris.

This is incredible.

"The only catch is that when luxury fashion houses open themselves up to a mass audience and lean heavily into the mainstream culture, they risk diluting their creative points of view and lowering the bar on craftsmanship so much that they start losing brand differentiation and alienating their core dedicated audience." This sums it up beautifully. And you're spot on.