Is Gen Z Capable of Good TV?

I Love LA, Entourage, and the trap of online criticism

I started dreading the discourse around Rachel Sennott’s HBO show long before it had a title. Unlike her bitter contemporaries — the twitter girls who sank into irrelevancy together with the platform, and open mic bros whose definition of “hustle” is limited to posting set clips on TikTok — I am eager to root for her. Shiva Baby, Bottoms, and Bodies, Bodies, Bodies make it hard to deny her talent and the burning wish to put something great on your screen even for those who find her increasingly “Hollywood it girl” persona cringe rather than endearing. But given how horny magazine editors and culture commentators are for a quippy descriptor, the lazy comparisons of Sennott’s pilot about “20somethings navigating life and relationships” to Girls were inevitable.

Over the past few years, “Girls for Gen Z” has been used to describe pretty much every new character-forward show that follows a group of young people which is funny, considering that “Girls for Gen Z” is just Girls. To say otherwise is to imply that the brilliance of the show is in its ability to speak specifically to millennials or capture millennials as a generation rather than what it actually is — create a set of unique, detailed characters, whose personal lives and careers are influenced, but not completely defined by the culture around them. They make the 2010s Williamsburg feel like a made-up world that you get to know a little better with every new episode rather than a real place and time that you have to have lived in order to enjoy the show.

Pop culture at large is full of these direct comparisons that box creatives in with expectations they didn’t sign up to live up to. If I Had Legs I’d Kick You has been described as “Uncut Gems for moms,” Addison Rae has been pitted against Tate McRae in a made-up competition for the title of Gen Z’s Britney, and every decent guy with a podcast has been called the Joe Rogan of their niche. The seemingly charitable impulse to chew up new talent and their work and spit them out in digestible for the broader audience terms is actually a disservice because it either measures the new names up against all the wrong people (imagine if the top guy in your line of work was a hack who platforms hateful narratives?) or stirs their careers in the wrong direction. One of the more interesting pieces of criticism circulating around I Love LA, for example, is a suggestion that the classic Hollywood track doesn’t give internet breakouts, like Rachel Sennott and her co-star Jordan Firstman, enough room to fulfill their creative potential because it pressures them to stick to outdated formulas rather than innovate.

Sennott herself has described her show as “Entourage for internet it girls” in a reference to a different HBO classic that follows a group of straight dudes from Queens trying to make it big in the early 2000s Hollywood — a premise so seemingly unrelatable to her target audience of “the girls and the gays” that it gives us a good idea of what to expect without putting the burden of direct comparison on the creator. And yet, after the third week of patiently waiting for I Love LA to kick into high gear, I binged the first season of Entourage and found a bunch of dudes who dabble in casual misogyny and homophobia, infinitely more watchable than a group of contemporaries, playing characters that are written directly for me and my peers.

Part of Entourage’s magic is that its long-gone world is peppered with recognizable details: the guys frequent Urth Caffe and Coffee Bean, kick it with young Jimmy Kimmel, and are in constant pursuit of the hottest status symbols of the moment, be it a pair of Uggs or a fat Rolls-Royce. They create these “he just like me fr” moments that make you chuckle and warm your heart with nostalgia. I Love LA attempts to create the same effect with Courage Bagels and Canyon Coffee which mostly backfires because of how overused these references already are in comedy skits and memes, circulating around the internet.

But more importantly, despite the flamboyant frontiers, the Entourage boys feel like real people, grounded by their simple upbringing and the dream to be part of something cool and acclaimed more so than rich. Each character plays into pop culture stereotypes — Vince puts on a Hollywood playboy act, Eric unconsciously slips into “the suit” persona — but by the end of the season, everyone, including Vince’s bro-ey agent Ari, takes off their toxic masculinity masks and comes together on a human level to make a great (indie!) film. I Love LA follows the same “friends over everything” narrative but so far, it’s still unclear what actually bonds its characters together, given that no one in the group, including its central protege Tallulah, has real interests or clear career aspirations. They move more like a bunch of punchlines stringed together for our entertainment, completely defined by their surroundings, than real people with independent inner lives.

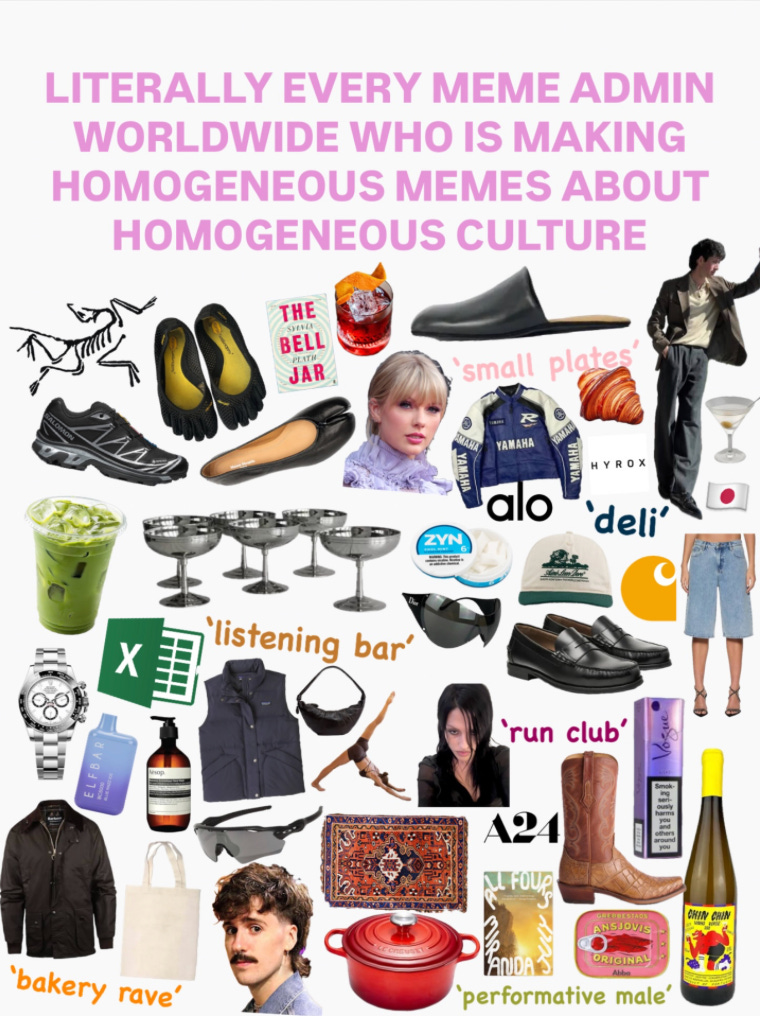

And maybe that is the message — to show exactly how vapid those who succeed at capturing attention despite the lack of real interests and talents are. The problem, then, is that it’s not exactly compelling — the internet has been kicking around the same idea for years by making fun of shallow characters, like the Silver Lake bro and the West Village girl, and it hasn’t pushed the laughing class much further creatively than the people they make fun of. “Meme admins mocking cultural sameness and trends while reproducing them in the same type of memes is the ouroboros of taste,” Ginny Ranu, the admin of @auniquecliche wrote in a recent post. “Algorithms reward imitation, audiences reward recognition, and we end up consuming the trends we create, until there is nothing original to eat.”

The prevalent impulse across the board is to make fun of how corny the mainstream is and then succumb to it anyway. Writers hate quippy descriptors but have to use them to bring visibility to their work. Artists and creatives that leverage internet fame to sign with music labels and secure movie and book deals feel stifled by how risk-averse and commerce-driven the entreatment industry is, but stay in it regardless because it validates them and sets them apart from influencers. Consumers who feel disengaged from the media and products marketed directly to bicoastal archetypes, spend more time making fun of both rather than working on or recommending alternatives. In that sense, I Love LA and the discourse around it are the perfect showcase of why the mainstream culture feels so stagnant despite plenty of new interesting talent cultivating in the niches.

“All [notable] culture has started from people who were like, yea, this sucks, I am going to do something else,” writer and culture critic W. David Marx said on a recent episode of Middle Brow. “You should get together with people who are like that, and you should take yourself out of the system for a while, so those ideas get fostered. And then hopefully, later, go and influence the entire system.” This is something that at least the first season of Entourage gets really well — the protagonist should be so curious about what happens if they revolt against the system and the expectations it places on them, that the perks of making the most of what it currently is can never outweigh the rush of making something cool and different together with their friends.

Love W David Marx and love middlebrow!!!

and thank you